(Also read the companion article, “Who’s running the Washington Post?” Both articles have been reprinted with permission from the Columbia Journalism Review, where they were originally published on September 27, 2022.)

For a news organization, being owned by an oligarch can be complicated.

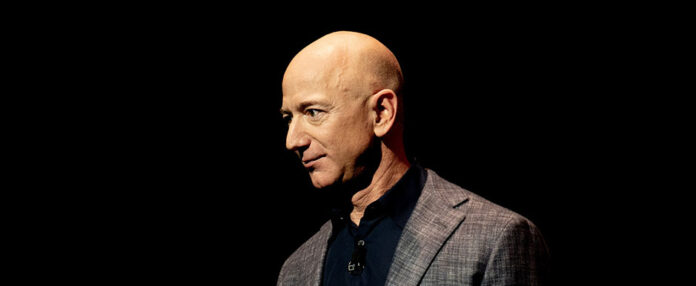

In 2013, when Jeff Bezos bought the Washington Post from the Graham family, those complications were not top of mind. The Post was in a downward spiral, sloughing off staff and flirting with irrelevance. Bezos’s money changed everything, bulking up the newsroom, revolutionizing its technology, and firmly reestablishing it as a dominant voice in the national media.

But the conflicts of interest are self-evident. Pretty much every public-policy issue the Post covers affects Bezos’s sprawling personal and business interests in material ways. The very existence of people as rich as Bezos clashes with the notion of economic fairness.

Recent moves have called renewed attention to how Bezos’s ownership constitutes a massive and almost entirely unaddressed conflict of interest for the Post.

In May, Bezos started posting highly provocative anti-Biden tweets, mocking the president’s moves to expose corporate greed and increase taxes on the wealthy. In July, he accused Biden of “straight ahead misdirection or a deep misunderstanding of basic market dynamics.”

Amazon has never been bashful about its political goals: its $20 million annual lobbying budget, which makes it the second-highest corporate spender in Washington, has been ruthlessly effective at fending off privacy protections, antitrust issues, internet regulation, tougher labor laws, and greater worker protection.

Amazon has become “almost a poster child for tech-fueled bigness run amok,” said Edward Wasserman, a media ethicist, professor, and former dean of the Graduate School of Journalism at Berkeley. And Bezos appears to have shaken off whatever reluctance he might have had to getting involved in politics, “picking gratuitous policy-related fights with the White House.”

“These billionaires, they like to be heard,” Wasserman said.

Now, nearly a decade after he bought the Post, Bezos has a leadership team at the company that is entirely his own. Bezos hired a new publisher early on, in 2014, picking Fred Ryan, a former Reagan administration official, chairman of the board of trustees for the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation, and a cofounder of Politico.

For years, however, the Post’s newsroom and opinion pages continued to be run by traditionalists held over from the Graham era: Marty Baron, the executive editor, and Fred Hiatt, who had already been editorial page editor for thirteen years when Bezos took over.

Baron retired last year, allowing Bezos and Ryan to hire their own new executive editor. They chose Sally Buzbee, the top editor at the Associated Press. Those who saw her as a potential champion of journalistic values have been disappointed; she has kept a low profile in the newsroom.

And in early September—nine months after Hiatt unexpectedly died—the Post installed a new editorial page editor, David Shipley, a journalist closely tied to another oligarch, Mike Bloomberg.

Throughout history, newspapers have frequently been owned by moguls—and readers were at times appropriately apprehensive. In this era, Rupert Murdoch has created a powerful media empire, which includes Fox News and the Wall Street Journal, and his influence has been considerable.

But Bezos is in a different league even from Murdoch. The world has never seen wealth like this before, and it has never been so interconnected.

Being owned by someone with such vast economic interests “is not compatible with the kind of independence we normally associate with independent news organizations,” said Wasserman.

Nobody at the Post—not Ryan, not Buzbee, not Shipley, not even a spokesperson—would answer specific questions about Bezos’s influence on the record. The paper did supply a general statement. “The Washington Post operates independently and discloses its ownership within articles when applicable. Our aggressive coverage of labor and business speaks for itself,” spokeswoman Molly Gannon wrote in an email.

The two biggest reasons not to be concerned about Bezos owning the Post are that the Post has a powerful and long history of independence; and that, according to multiple sources, Bezos has never demonstrated an inclination to interfere with the Post’s journalism.

“Just because there is a potential for a situation where Bezos influences the newsroom, that doesn’t mean it’s going to happen,” one editor told me.

Several reporters I spoke to said there was no evidence that Bezos has ever weighed in on anything other than strategic matters focused on the business side. But one acknowledged the possible impact of self-censorship. “What I feel most is a little bit of reluctance to take him on,” the reporter said. “It certainly can complicate things.”

The Twitter War

As soon as Bezos started a Twitter war with President Biden, long-neglected concerns about his influence on the newsroom became considerably less abstract.

It all started with this tweet, on May 13:

The newly created Disinformation Board should review this tweet, or maybe they need to form a new Non Sequitur Board instead. Raising corp taxes is fine to discuss. Taming inflation is critical to discuss. Mushing them together is just misdirection. https://t.co/ye4XiNNc2v

— Jeff Bezos (@JeffBezos) May 14, 2022

As Julian Epp noted in the New Republic, Biden’s tweet “didn’t name Amazon or Bezos, but Bezos felt compelled to respond all the same.” (The reference to the “disinformation board” was based on a right-wing conspiracy theory.)

Two days later, Bezos tweeted that “the administration tried hard to inject even more stimulus into an already over-heated, inflationary economy and only [West Virginia senator Joe] Manchin saved them from themselves.”

He accused Biden of misdirection.

As the Post itself reported (to its credit), “The White House responded by pointing out that Bezos’ attacks emerged days after Biden met in the Oval Office with the labor leaders behind Amazon’s unionization drive, which the company has vehemently opposed.”

The White House also pointed out that Bezos would pay an additional $35 billion under the administration’s billionaire tax plan.

Bezos shot back with another tweet, mocking the White House response.

The next day, after Post opinion writer Catherine Rampell—somewhat out of character—ridiculed progressives who argue that the greed of monopolies and large corporations amounts to price gouging, Bezos retweeted her column.

And in early July, Bezos responded contemptuously to Biden’s plea to gasoline producers to stop exploiting inflated market prices. Biden had implored them: “Bring down the price you are charging at the pump to reflect the cost you’re paying for the product.”

“Ouch,” Bezos wrote. “Inflation is far too important a problem for the White House to keep making statements like this. It’s either straight ahead misdirection or a deep misunderstanding of basic market dynamics.”

(Bezos was wrong. “There is not much disagreement that many companies have marked up goods in excess of their own rising costs,” Lydia DePillis wrote in the New York Times. Oil companies posted record profits in the second quarter, precisely because they raised their prices so much even as their costs remained stable.)

After the first spate of tweets, Andrew Perez and David Sirota wrote on the leftist Jacobin website: “If you were looking for a digital era version of Citizen Kane behavior, this is it.”

Jack Shafer, Politico’s media writer, acknowledged that “Bezos’ outbursts could also unfairly complicate life for his own journalists; if the paper produces critical coverage of the president—often more than justified!—Post skeptics will wonder if it was marching orders from the boss.”

Most notably—given Bezos’s views about Biden and inflation—Post news coverage of Biden’s domestic policy has consistently been more negative than its competitors’. The Post doesn’t hesitate to identify inflation as a Biden problem, often while ignoring that it’s a global problem. Its political reporters have frequently declared inflation to be the central issue of the midterm elections (which it is not).

The New York Times has similar issues, but comparing their coverage of positive job reports, for example, one finds the Post almost always casting the news in a worse light for Biden than other mainstream publications.

To some journalism watchers, the most backhanded defense of the Post is that it has not buckled to Bezos—it’s always been this way.

“Bezos didn’t need to make any changes; the Post had already adopted the establishment, pro-corporate view,” said Robert W. McChesney, the author of several books on media and politics. “Its editorial line was pretty compatible with his on the issues that mattered to him.”

Jeff Cohen, an emeritus journalism professor and cofounder of fair, the national media watch group, explained it this way: “The main thing that the liberal media doesn’t cover well is victims without victimizers. They’ll talk about poverty, and systemic racism, but they’ll never talk about who’s benefiting from it. Who’s behind it? They don’t name the names of who’s benefiting. And on some social and economic issues, Bezos is one of the main beneficiaries.”

Bezos Culture

Nobody is suggesting that Bezos is specifically or directly telling Post reporters and editors what to write or how to write it. Indeed, Bezos is widely seen as uninterested in what the newsroom produces, as long as it gets attention and advances his plans for the Post to become a global brand. (He was, for instance, the driving force behind the Post setting up two new “global hubs” in London and Seoul that take over operations when Washington winds down.)

But he doesn’t have to say anything to make things happen. “That’s not how power is typically exerted,” said Victor Pickard, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg School for Communication. Rather, “there are more subtle kinds of ideological policing,” he said. “Journalists internalize broader power relationships that can help steer media coverage in particular ways.”

“At a minimum, the positions he’s taking are going to change the way staff at the Washington Post are perceived,” Wasserman said. “Right now I’m just saying ‘perceived.’ But it would be grossly unrealistic for us not to imagine that his preferences are going to have an important influence over the way the newsroom operates.”

That’s why the tweets are so troubling. They make it clear what Bezos wants to hear. Journalists are not immune to such pressures. In fact, quite the opposite. “They’re very sensitive people. They spend a lot of time sniffing the wind,” Wasserman said.

“The values of the owner tend to be communicated subtly,” said McChesney, the author of several books on media and politics. Those who don’t pick up the signals “get weeded out along the way.”

(I know a little about that, having been fired from the Post in 2009 from my job as White House Watch columnist after failing to be sufficiently deferential to newsroom culture.)

A Better Way Forward

The Post needs to explain to its readers how it intends to address the conflict inherent in the fact that it’s owned by the world’s richest man. The idea, Pickard said, is “to force this to become conscious, to make what’s implicit more explicit, to make it more public.“

Bezos issued a pledge upon buying the Post nearly ten years ago, saying that “The values of the Post do not need changing. The paper’s duty will remain to its readers and not to the private interests of its owners. We will continue to follow the truth wherever it leads, and we’ll work hard not to make mistakes. When we do, we will own up to them quickly and completely.”

But there’s nothing related to Bezos’s ownership in the Post’s updated, official “Policies and Standards” document, which includes an ethics policy. As Rodney Benson, an NYU professor who researches the effects of media ownership, explained: “There’s a long section about conflicts of interest—but it’s all about journalists’s conflicts of interest, relatively little things, in terms of taking gifts or whatever. It says nothing about how the Post should cover its owner or its owner’s conflicts of interest.

“There’s nothing on the website that says ‘Here’s how we should deal with the fact that we’re owned by this billionaire who has all these outside interests,’” Benson said. “I think they need to add some more provisions on the relationship with the owner.”

Benson noted that French publications, like Le Monde, publish codes of conduct that specify how their editorial freedom is protected from interference by the owners. So, for instance, the shareholders “signed a charter of ethics guaranteeing the newspaper’s complete editorial freedom” and agreed to “not take part in editorial choices” and to “refrain from commissioning an article and from giving instructions to modify an article or prevent its publication.”

The paper also includes a statement of principles:

Le Monde defends humanist and progressive values. It supports democracy against all forms of authoritarianism. It is pro-European and defends human rights and civil liberties, the pluralism of ideas and respect for the environment. It is not linked to any political party. Its editorials, which are not signed, are the opinion of the entire editorial staff. It strives to keep public debate alive, notably by publishing opinion pieces written by people outside the editorial staff. In reading Le Monde, the reader is empowered to freely form an opinion.

The Post could follow suit and publish a statement of its core journalistic values—emphasizing those that embody its independence from an oligarch owner.

Kelly McBride, senior vice president of the Poynter Institute and public editor for NPR, suggested that Post editors announce an “extra layer of editing” for stories related to Bezos’s business interests. And she said the editors should find ways to hold themselves accountable to the reading public. “I do believe that this is a great forum for a public editor.” (The Post eliminated its ombudsman position a few months before the Bezos purchase.)

Some critics, myself included, would like to see Buzbee publicly announce that she is committing additional resources to cover issues where Bezos’s interests are implicated, like workers’ rights, the damage caused by monopolies, and income inequality.

“Increasing coverage in areas that you know would be vexing to your owners and putting extra editorial resources to those areas may well mollify those who are wary that the newsroom is being corrupted,” Wasserman said. “It’s a way to manage the problem in a way that very much advances and doubles down on a traditional view of news ethics. It does assert in a very compelling way that we’re aware that our ownership could be a problem, and this is what we’re doing about it.”

What else could the Post do?

Dan Kennedy, a journalism professor at Northeastern University, credited Bezos for having “a good track record of not mucking around in the news section.” But he said if the Post editors really wanted to resolve the conflict-of-interest question, “I suppose nothing would answer the question more thoroughly than if they suddenly unveiled a real ass-kicking story about Amazon—a real in-depth piece of enterprise reporting that reflected pretty harshly on their owner. That would answer the question pretty thoroughly, wouldn’t it?”

Cohen has a specific suggestion. He is still fuming about a ridiculous 2017 Post “fact check” of a statement, by Bernie Sanders, that the six wealthiest people in the world—which of course would include Bezos—have “as much wealth as the bottom half of the world’s population.” The Post gave it “three Pinocchios” because although it was “technically correct,” it “lacked nuance.”

“If they fact-checked Bernie on the six wealthiest people, then they could do a fact-check on their owner regarding taxation and Biden. That would be the right thing to do,” Cohen said.

Bob Kaiser, a former managing editor of the Post, said the conflict-of-interest concerns could be “easily addressed, probably with some evergreen statement that Bezos and the editors could agree on.” And he said he doesn’t think the Post should alter its course to prove anything. “I think the Post should cover the news aggressively, always. I don’t want to have some special mission based on who’s the owner, either way.”

One thing that sure couldn’t hurt, of course, would be for Bezos to hold his tongue. “The best media owners will be very, very careful,” McBride said, “and when they’re preparing to say something that will obviously cause people to question the independence of their media organization, they will include a caveat that says: ‘I have hired really good editors, and they run the paper with a loyalty to the audience. They do not serve my interests.’”

And then there’s a long-term solution that would erase any doubts about independence: “Ideally,” McChesney told me, “what you would love to get from Bezos is a formal statement setting the funds aside.”

His advice to Bezos: “Set it up to be truly independent. Make it a nonprofit. You get a huge tax write-off.” Then, “get out of the way and go do it in other cities.”

Putting the entire operation on a nonprofit footing would also guarantee the Post’s independence for eternity, regardless of what Bezos’s heirs might have in mind.

As long as Bezos is the owner, “you’re dealing with a problem you don’t have the capacity to solve—you can only manage it,” Wasserman said. “And whatever you do—even if you go out of your way to do stories sympathetic to the labor movement within Amazon—you’re going to be seen as asserting an independence that nobody thinks you have.”

“This is not just the Post’s problem or Jeff Bezos’s problem,” Pickard said. “This is our problem as a democratic society.”

(Also see: “Who’s running the Washington Post?“)