What do you do when you’re covering a lying, bloviating politician who revels in attention, good or bad?

Ignoring him is impossible. Covering him neutrally is harmful. Even covering him critically enhances his status and fuels his anti-media attacks.

So you’ve got to try something different – specifically when it comes to covering his lies and provocations.

As a fellowship project at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, Michael Hauser Tov, chief political correspondent at Haaretz, wrote a playbook for how to cover what he calls “populists” in a journalistically responsible way.

I don’t agree with some of his nomenclature. For one, I don’t like calling people like Trump “populists”. To me, a populist is a politician who harnesses the passions of ordinary people, not necessarily in a negative way. I consider Bernie Sanders a “populist” — in a good way.

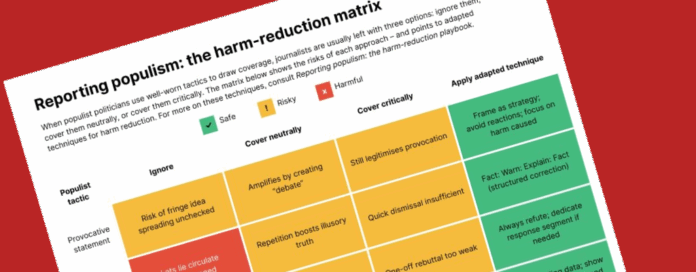

But the heart of Tov’s work – an excellent chart and a stellar checklist — is spot on. It’s worth clipping and saving. (There’s also a white paper, where he expands on his thinking.)

Covering Provocative Statements

Consider, for instance, how to cover a provocative statement.

Ignoring it allows it to spread unchecked. Covering it neutrally, or simply as a matter of debate, amplifies it.

Even covering it critically, and focusing on negative reactions to the statement, creates what Tov calls in the white paper “a position-versus-position dynamic” that “represents a major victory for the populist politician, as it transforms their statement into legitimate political discourse and normalizes it.”

He explains further: “the populist’s goal is not necessarily to gain sympathy, but to gain legitimacy, establish their status, and bring ideas from the margins into the mainstream. In such cases, the positive effect of media exposure is more important to them than the negative effect of the tone they receive in coverage.”

So journalists should “avoid framing the provocative statement as part of a legitimate political debate,” Tov writes.

He suggests framing it as part of a strategy, instead. “Report the statement itself, its aims and effects (especially on ordinary people),” Tov writes.

He quotes from an interview he conducted with the media critic Margaret Sullivan: “The way you don’t want to cover it is just to go to the outrageousness of it. It’s outrageous. But you need to put it in the context of ‘here’s a politician who has thrived on division, and he took it a step further today when he did this…’”

Cover provocative statements like mass shootings, Tov suggests. Think about how to reduce the “contagion effects.” Focus on the victims.

Covering Blatant Lies

Ignoring a blatant lie lets it circulate unchallenged. Covering it neutrally is a form of repetition. Even a quick dismissal is insufficient.

Instead, Tov writes, journalists should correct the lies with what he calls FWEF, which traces its origins to a 2020 publication called the “Debunking Handbook.” It’s a slight variation on what’s become known as the “truth sandwich.” FWEF is:

- Fact. Lead with the truth: make it simple, concrete, and plausible.

- Warn. Warn beforehand that a myth is coming and tell it only once.

- Explain. Explain how the myth misleads.

- Fact. Finish by reinforcing the fact: multiple times if possible. Make sure it provides an alternative causal explanation

What about putting someone like Trump, who lies all the time, on the air?

Before broadcasting a live interview with a populist politician prone to controversy, or before airing their speech when manipulation is expected, remind viewers manipulation is to be expected: this isn’t their first lie. This isn’t their first conspiracy theory. This isn’t their first dog whistle. Advance warning has proven more effective than after-the-fact correction.

More Suggestions

Here are some more items from Tov’s checklist. (Forgive the British spelling and examples; the Reuters Institute is based at Oxford University.)

- Avoid false balance. If you platform two sides, show the real distribution of expertise or public support (e.g., “60 economists against, one for”).

- Show the true scale of events. Replace “political firestorm” with numbers (“five MPs criticised”). Quantify; don’t dramatise.

- Name the behaviour, not the category. Skip the softened catch-all language (“populist”). Say what they did: spread a conspiracy theory; made racist statements; incited harassment.

- Keep interviews tight. One or two topics, persistent follow-ups. Don’t let them “flood the zone” by smuggling unchallenged claims into the segment.

- Protect the right of reply. Cut irrelevant attacks and falsehoods from their reply; add your correction. Right of reply isn’t a licence for propaganda.

- Respond to anti-journalistic attacks. Silence reads as agreement, not objectivity. Build short segments that dismantle the claim against your newsroom.

Covering Trump in particular requires additional strategies that Tov doesn’t get in to.

For instance, in an article like this one in today’s New York Times – about Trump “determining” that the U.S. is now at war with drug cartels – reporters need to make crystal clear at the very top that what he’s doing is illegal and unconstitutional. That shouldn’t show up starting four paragraphs in, ascribed to critics.

Caveats about Trump generally should include not just that he lies all the time, but that he often has no idea what he’s talking about, that he is easily deceived or manipulated or both, and that he may be seriously unwell.

Trump coverage needs to situate his every act as part of his quest for dictatorial power.

But Tov’s playbook is nevertheless excellent, and I hope it some of our newsroom leaders take it to heart.

(Hat tip to media critic Jay Rosen for alerting me to Tov’s work.)