Every day, more Americans are getting sick, more Americans are dying, and all over the country, people are staying in their homes, fearful and uncertain, hoping that things will be better soon.

At a time like this, we need information – daily. We need updates, and explanations, and reassurance. We need to know the plan. We need to know the future.

We get none of that from Donald Trump. Instead, we get endless hours of lies, hyperbole, insults, self-praise, all endlessly repeated, all entirely lacking in credibility.

The “most recurring utterances from Mr. Trump in the briefings are self-congratulations,” writes the New York Times. “The president has offered little in the way of accurate medical information or empathy for coronavirus victims, instead focusing on attacking his enemies and lauding himself and his allies,” notes the Washington Post.

The briefings are now in limbo. Rumors swirled over the weekend that Trump had finally sworn them off. But he was back in full force on Monday, lying and spewing as many canards as ever. On Tuesday, he offered a condensed version of his greatest misinformation hits. The rest of the week is up in the air.

But we need a daily briefing. The right kind of daily briefing.

What we need to know

Here is what we need to know.

We need to know the latest numbers. How many new cases have there been? How many ER visits, hospitalizations, ICU beds filled? How many more people have died?

And what do these latest numbers indicate? Are they moving in the right direction? Are they moving fast? Are there big regional and demographic differences? Where are there signs of hope? Where is the data discouraging?

What’s not going well? What is troubling the officials and experts charged with monitoring the nation’s progress through this crisis? What is making them happy?

What has the government done today to try to make things better? And what is the context for those achievements? Tell us what’s been achieved, yes, but also what we still need. Numbers out of context are meaningless.

The briefer, who should attend the task force meetings, should also be prepared to discuss what else came up today, and to address any previous misstatement that need to be corrected.

There should be reports from any related groups – most particularly from whatever group is charged with managing and dramatically increasing the supply chain for testing. How adequate are supplies? What are the roadblocks? What is being done to overcome them?

What are the latest medical findings? Do we know anything new about how the virus works, or what treatments might help?

There should be a daily reminder of the plan — the roadmap, the goals, whatever you want to call it — and of how far along we are. What do we still need to do?

How will we know when it’s safe to come out again?

There should be a clear and detailed delineation of the federal government’s responsibilities. And a reminder of what’s next.

And what of the rest of the world? What are we doing for them? What are they doing for us?

That’s the hard-data part.

The human part

There also ought to be a human part.

The briefing should include a solemn recognition of the incredible losses being experienced by the American family. There should be expressions of empathy and sorrow. Maybe even a few stories about the people who have passed.

And there should also be words of hope, and inspiration: exhortation and appreciations of shared sacrifices, maybe the recounting of selfless acts taken by the too-often unsung heroes of this pandemic.

The message should be inclusive, and generous, and forgiving: We are all in this together. It should include what one critic noted is so terribly absent in Trump’s remarks: “the language of transcendence, what we have in common.”

Questions

Then it’s time for questions. Ideally, the questions would come not just from the political reporters who make up the White House press corps, but by phone or video from medical and science reporters, from local reporters, maybe even from public interest groups or the public directly. There could be a daily FAQ.

After a response to a question, the person who asked it could be asked if they feel they got an actual answer, and should be given a chance to follow up.

There should be no room for politics. No room for insults. No us vs. them. No bragging. No victimization. No attacking the questioner. And no endless repetition of ridiculous talking points.

What that all adds up to, of course, is that there should be no Trump.

Who does it then?

We could just take Trump and Pence out of the mix. But who would lead the briefing?

Historically, such briefings have been the domain of the CDC, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It’s been sidelined this time around, and the one person speaking on its behalf – the director, Robert Redfield — is a Trump appointee and a hardcore right-winger who initially downplayed the crisis and has parroted his patron since.

Is there someone besides Redfield at the CDC – someone not complicit in the center’s early testing failure – who could step up?

It certainly shouldn’t be a political appointee.

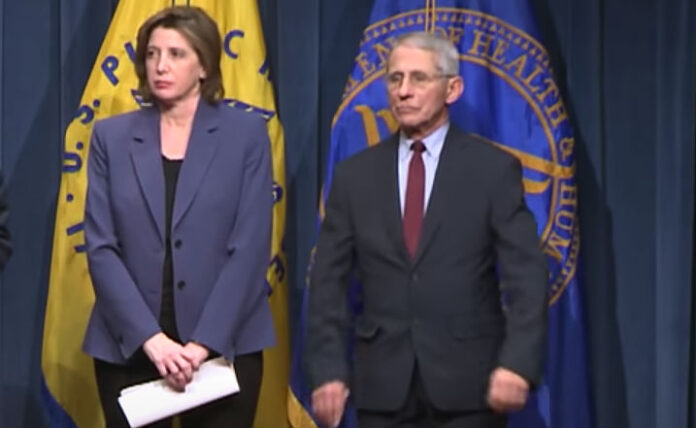

Maybe it’s Anthony Fauci, from NIH’s National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases.

Or what about Nancy Messonnier? The then-director for the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at the CDC gave briefings on Feb. 14, 21, 25, 28 and 29, as well as March 3 – until Trump pulled the plug because Messonnier had acknowledged that community spread of the virus in the U.S. was an inevitability, back when he was still predicting it would go away by itself.

Possible role models include California Gov. Gavin Newsom, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, and New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern.

Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne Jr. has an intriguing suggestion: “let’s have a bipartisan coalition of responsible governors pick one of their own to lead a daily briefing aimed at the whole country.”

What’s it in for Trump?

Why would Trump even consider allowing such a thing to take place? What’s the political advantage?

Realistically, he’ll never give up the limelight — the visual cues that suggest he is actually in control.

But it’s not like he’s doing any of the real work now anyway.

Trump would still need to sign off on major initiatives, presumably. So he could still maybe give a weekly address to take credit for things when the real team takes a day off – call it six no Trump.

He would still be handling all the economic news, which is really what matters to him the most.

And he would arguably be the single greatest beneficiary of increased public confidence that the crisis was being handled competently by qualified officials with expertise and the greater public interest at heart.

His approval ratings certainly wouldn’t go down.

Trump’s consistent yearning throughout this crisis has been an easy, quick fix. Outside of fantasy solutions, putting someone else in charge is the closest thing there is to putting it behind him.

Please comment on what I watched on tv: DeSantis says no more reports on deaths in Florida. As I read on Twitter: Is DeSantis worse than Trump?