It’s been an infuriating mystery to me for a long time now: Why aren’t mainstream political journalists taking a more aggressive approach to explaining the threat to democracy? Especially with such a big step potentially coming next week?

The threat is awfully clear. I think it’s also one hell of a news story. So why are they just covering it like another partisan fight?

Here at Press Watch, I have often speculated that it’s because of the dictums of hidebound editors who feel they should remain above the fray. My thinking was that if those editors just freed reporters of the obligation to “both-sides” every political issue, they would spring into action.

But what if most of the people in those newsrooms actually don’t feel that the threat to democracy is real? What if they’re actually not alarmed?

What if they look out at the political sphere — increasingly filled with election-denial, voter suppression, political violence, unaccountability to the law, enthusiastic abuse of public power to punish enemies — and think: Eh, it’ll blow over, it doesn’t affect me?

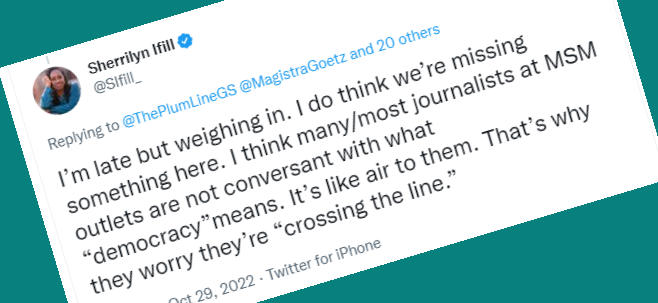

That was one of several theories that ended up being discussed recently in a thought-provoking impromptu Twitter colloquium that included Sherilyn Ifill, Craig Newmark, Soledad O’Brien, Nikole Hannah-Jones, Ruth Ben-Ghiat, Greg Sargent, and Jay Rosen.

It started with my post wishing for a newsroom full of journalists really energized to expose, explain, and sound the alarm about how dangerously delusional, deceptive, racist, misogynistic and authoritarian the GOP has become.

That doesn’t mean a partisan newsroom. It means reporters who see what’s going on and want to warn people, rather than essentially running cover for dangerous demagogues.

It means reporters and editors who don’t try to stay above the fray when the fray is about democracy.

I cc’d a bunch of people I respect and asked them: Is this really undoable?

Craig Newmark, the founder of Craigslist who has become a major philanthropist focusing on promoting trustworthy journalism, weighed in pragmatically, writing: “Maybe doing so effectively is.”

Then Soledad O’Brien, the documentary filmmaker and former CNN anchor who has become an outspoken press critic, made this astute observation: “I think it’s more a question of will than of talent.”

It’s also a question of remembering who you are, she added. “When people forget that—in fact—they ARE on the side of democracy and freedom of the press. Of truth. Of accuracy.”

Jay Rosen, the NYU journalism professor who has coined many of the phrases that are central to progressive press criticism – the “view from nowhere” the “savvy style“— sadly concurred, writing: “This kind of forgetting is one of the worst lapses there can be in journalism.”

But it was Sherrilyn Ifill, the extraordinary civil rights lawyer whose Twitter feed is one of my moral touchstones on social media, who raised the idea that maybe these journalists simply can’t imagine a loss of democracy — or their privileged role in society.

“I think many/most journalists at MSM outlets are not conversant with what ‘democracy’ means. It’s like air to them. That’s why they worry they’re ‘crossing the line,'” Ifill wrote.

Ruth Ben-Ghiat, an expert on totalitarian regimes, agreed. “This is my impression sometimes when I am interviewed about democracy and authoritarianism,” she wrote.

And then Nikole Hannah-Jones pointed out what’s missing from those newsrooms.

“Yes. This is why Black journalists and the traditions of the Black press are so critical,” she wrote. “We know that democracy has been and is always contested and fragile, and at times missing altogether.”

Hannah-Jones, as I’ve written before, is a brave and brilliant truth-teller. She now runs the Center for Journalism & Democracy at Howard University, which is holding a Democracy Summit on Nov. 15, in part to reexamine “the journalism profession’s central concepts of fact, objectivity, fairness and balance.”

The summit takes as a given that, in the face of “anti-democratic forces,” aiming to preserve balance is “an unworkable approach and a crisis for our profession and our country.”

Hannah-Jones’s tweet suggests that the lack of diversity in our top newsrooms – often acknowledged as a representation problem, and as creating a blind spot about the role of race and racism in politics – also creates a sense of false comfort about our democracy.

O’Brien gave Ifill an amen. “Yes. Every time somebody tells me ‘this is not who we are’ or ‘I’m absolutely shocked by this!’ I feel like maybe they should read a book about American history,” she wrote.

Matthew Sheffield, a formerly right-wing journalist who now works for the left-wing Young Turks online news show, raised an issue related to the urban, upper-class backgrounds of so many elite journalists: “I think the root of this issue is that the vast majority of journos never had any real contact w the religion-based authoritarianism which took total control of the GOP after the Tea Party. It’s still not real to them,” he wrote.

Press Watch is devoted to the principle that in the current political climate, journalists need to change the rules of the game. That’s never been more clear, as this brain trust made clear.

“When the two major political parties were at least in agreement that democracy should be protected it was easier,” Ifill wrote. “Once Trump erased the lines & the Republican Party abandoned allegiance to democracy, it forced a set of questions many journalists are ill-equipped to answer.”

Rosen summarized some of his conclusions: “I agree. Their practices ran on a mental picture of two roughly similar parties with different ideologies that fought it out during elections to see who could rouse more voters to their side. As the GOP abandoned its allegiance to democracy, this consensus understanding gave way,” he wrote:

“When the ‘don’t take sides’ commandment meets a lopsided story like, ‘we have a two-party system and one of the two has turned anti-democratic,’ people in newsrooms hesitate because they are confronted by what feels like a conflict in their code: stay balanced vs. say what is,” he continued.

The real-life result is garbage like a front-page New York Times story I wrote about last week, in which the author wrote that “just what is threatening democracy depends on who you talk to.” Or, like an execrable Washington Post article on Monday claiming that “people on both sides of the partisan split” share the “hope that the country can be put back together again.”

Greg Sargent agreed with Rosen and, perhaps unwittingly, perfectly described the difference between his reported opinion column for the Washington Post, which is unflinching in its descriptions of the dangers we face, and the work of his colleagues on the news side.

“The idea that ‘one party is abandoning democracy and the other isn’t’ requires journos to arrive at a baseline conviction on what democratic values are and why they matter, and that’s not something that was expected of them before,” Sargent wrote.

Ifill’s comments made me wonder if maybe the newsroom poohbahs really think that all of us who are worried about the threat to democracy are just being shrill and hysterical. That would be crazy, but also very true to type.

Rosen insisted that it’s more that they think it’s a partisan issue, and therefore needs to be treated symmetrically.

I think it’s some of both.

Newmark asked a deceptively simple question: “When a publication engages in false equivalence, both-sidesism, or otherwise amplifies falsehoods, could professional journalists call that out?”

They could, of course. And some of us do.

But the owners of news organizations have largely fired their “public editors” – who once used to bring widespread public concerns to their attention. Professional media critics – and there are vanishingly few of us – are marginalized by elite journalists, who turn out to be remarkably defensive.

And the people within these institutions – even once they leave – seem to feel that collegiality requires them to keep quiet about the failings of their profession. That’s a terrible mistake. We all must speak out, because the stakes are simply too high.

They haven’t forgotten anything; for most of them, an elite occupation like a career in journalism, is not a job you are supposed to do, not a calling that imposes obligations; it is the reward for personal virtue shown by getting those straight-As at whatever elite institution they went to. It is their particular sweet gig that they earned. Something they are entitled to. Just like every other elite in our society. They consider themselves fellow class-members with those they report on, and don’t believe they are at risk.

This is a consequence of Journalism being transformed from a blue-collar job to an elite occupation requiring a college degree. A further consequence is that that they don’t talk to, don’t identify with, don’t have empathy for ordinary people, and certainly don’t get their information by talking to them. It is kind of tough to find out what’s really going on and report it, when all you ever do is talk to fellow elites. You tend to only get fellow elites version of the story.

I think it’s more than people thinking it can’t happen. It’s like global warming: it’s inconvenient to admit that it has been happening for a very long time.

There have been a long series of attempted coups designed to destroy the principle that elections matter. The assassination of Abraham Lincoln brought white supremacist Andrew Johnson to the presidency. There was the Business Plot to remove FDR. But these were plots from outside the Executive Branch, and modern journalists wouldn’t necessarily connect these to modern attempts at overthrow.

Watergate, in which the sitting president used his power to manipulate an election, was probably the first inside job; it’s telling that Roger Stone was a player then and now. Newt Gingrich wanted to simultaneously impeach Al Gore and Bill Clinton so that he could become president. Bush v. Gore upended 200 years of precedent to stop a state from counting votes and certifying an election. These are the soil in which the plan for the coup incubated. And journalists have been carefully avoiding looking at the common thread: the desire to replace voters with a few decision-makers.

Democracy requires a leap of faith. Instead of believing, as do the British, that the “best people” should run things, we have from the beginning believed that including as many people as possible (within our limited imaginations of who constitute “people”) would result in wiser decisions and more national unity in getting through difficult times. Democracy is like a church choir: perhaps only a few of the voices are skilled, and perhaps many are off-key, but somehow they blend together into something beautiful.

Why can no journalist see this and say this?

A friend of mine, back when he was a young journalist in communist Poland, got a chance to chat with David Broder and Cokie Roberts. Broder told a story about a young colleague who published a story and was fired, and my friend asked why Broder didn’t try to protect him, as his editor back in communist Poland would have tried to protect him. Broder stared at him blankly.

All Cokie wanted to talk about was the architectural model of her fabulous new home.

Because their jobs are a reward, not an obligation, it would not even occur to them that there is a legitimate reason to risk losing them by publishing the wrong story.

They cosplay that they are serving the public interest and believe a real journalist can do that without risking anything.

These people are scabs to real journalists. Their gutlessness in a job that requires it makes that much harder real journalists to survive.

NPR had some panel news show convening in the local theater. They were all hyperventilating about the ‘cheap shot’ Bernie Sanders supposedly took at the WAPO. I would have liked to ask; “do you guys never stop rehearsing for that sweet, sweet, MSNBC gig?”

Followed by;

“What is the story that got you fired that you are most proud of?”

Until there is widespread and obviously politically motivated violence and killing them the threat of fascism or whatever term one chooses for what will be one party rule, then nobody who works for a corporation will acknowledge it. It will just be both sides till then for them. This is far more a cultural thing about perceptions than an conscious thumb on some scale in the “mainstream media”. Not the culture of the country writ large but the culture of people who get hired and rise in corporations. In media corporations that applies from editors on down to reporters. Not that American culture isn’t strongly fascist for it is.

Fascism is a vital part of the America so the media market serves it. It’s the market speaking

Fascism being a love of not just of the country so much but a deep love of The Nation. A Nation being more than just a country, more than just a politically defined State or government. Fascism is a love of a native people, united by blood, soil, history and religion.