There’s a difference between a leaker and a thief. It comes down to motive.

Leakers “leak” because they want something to become more widely known. The most celebrated leakers are whistleblowers, who believe people have the right to know what is being kept secret from them, either specifically or generally. They are often heroes. Leakers are public-spirited.

Thieves just post (or sell) secrets because they can. They are self-serving. They don’t intend those secrets to go beyond their specific audience.

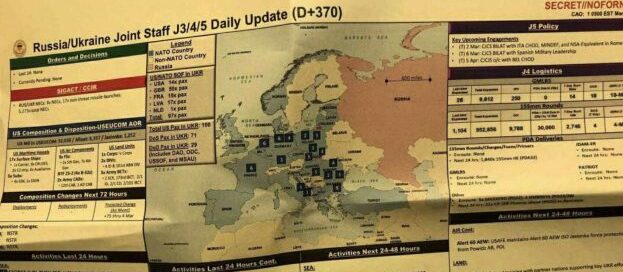

The highly sensitive classified documents apparently posted months ago on a gamer discussion board by a white supremacist National Guardsman trying to impress a bunch of teenage boys may technically have “leaked” out. There was obviously a hole in the Pentagon’s security, and he exploited it.

But the documents weren’t given to the public or to journalists for the greater good. They are not what journalism normally celebrates as “leaks.”

That doesn’t mean journalists should be heeding National Security Council spokesman John Kirby, who on April 10 told White House reporters to ignore the new information. “It has no business, if you don’t mind me saying, on the pages of — front pages of newspapers, or on television,” Kirby said. “It is not intended for public consumption and it should not be out there.”

Once documents like this are public – and, assuredly, already in the hands of other intelligence services — it would be wrong for journalists to avert their eyes just because their provenance is unseemly.

Indeed, these contain hugely newsworthy revelations, which fully deserve the kind of coverage they are getting. That includes significant revelations about U.S. assessments of the war in Ukraine. They will also, hopefully, reignite debate over whether it is really appropriate for the U.S. to be listening in on every communication in the world (as long as it’s not in the U.S., Canada, Britain, Australia, or New Zealand.)

But as David E. Sanger wrote in the New York Times on April 9, the documents also include “detailed targeting data,” and descriptions of “coordinating the long, complex logistical train that delivers weapons to the Ukrainians.”

The documents are increasingly being referred to as “The Discord Leaks,” after the server on which they were initially posted. It’s a great term, with a subtle double meaning. But maybe they should be called something less noble, like the Discord Breach. Or something with “purloined” in it. Or, because many seem to be products of the Pentagon’s Joint Staff, the Joint Staff Papers.

“The neutral, bureaucratic term for it is ‘unauthorized disclosure,'” secrecy specialist Steve Aftergood told me. The word “leak” is “a colloquialism that can be misleading,” he said. “This doesn’t fit even the loose definitions of the term. It’s just a convenient shorthand.”

He defined a normal leak as providing controlled information to a journalist or an activist.

“The motives here are still obscure, but they’re not what we would call whistleblowing or journalism. They are just sort of an act of defiance for no clearly defined purpose.”

Naming the trove in a way that telegraphs its source is important.

When we think back to the emails from the Clinton campaign that we initially wrote were “leaked,” we realize that was a mistake. They weren’t sent to reporters by an insider who legitimately had access to them. They were hacked by the Russians as part of an attempt to influence the election. That was significant.

And there are different kinds of leaks, as well. One distinction is how they are released, and to whom.

The ailing Daniel Ellsberg was a hero, leaking a secret government study of the Vietnam War known as the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times in 1971, to expose the administration’s lies.

Another good example is Edward Snowden, who illicitly copied a trove of secrets involving the NSA and its massive surveillance infrastructure because he was horrified at what the government was doing and how little the public knew about it. And he leaked to selected journalists — on the condition, which they honored, that they would only publish material that was in the public interest.

Chelsea Manning leaked way more than she had to – and to Wikileaks, which released far more than journalists probably would have — but very much in the cause of transparency during brutal American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Daniel Hale, a former intelligence analyst, leaked “The Drone Papers to writer Jeremy Scahill in 2015, to let the world know that the vast majority of people killed in U.S. airstrikes were not the intended targets. He has been in prison since July 2021.

The enormous distinction between a public-spirited leak and a self-serving theft is one of the many reasons why journalists largely oppose the Justice Department’s policy of charging anyone who reveals secrets with violating the Espionage Act, a World War I-era law that does not allow defendants to even make the argument that their actions were in the public interest.

“Some unauthorized disclosures are good, and highly desirable,” Aftergood said. “Others create or exacerbate threats. A leak of a government program can be a good thing if it promotes accountability and democratic intervention.”

But, he said, “the leak of a design for weapons of mass destruction or operational details of authorized operations can be destructive or even nihilistic.

“I think most of these disclosures, or many of them, fall in the nihilistic category.”