Great political journalism requires the courage to state the obvious.

Sadly, our access-dependent, approval-seeking, risk-averse, group-thinking elite Washington press corps often doesn’t have the guts.

Most of its members have survived and risen to the top of their profession by carefully navigating a path that avoids the kind of definitiveness or stridency that offends important sources and makes their bosses nervous.

Think of elite political Washington as one big ongoing cocktail party (which it oftentimes literally is.) Who wants to be the skunk?

This is hardly a new phenomenon. For example, the press corps during the George W. Bush years, at least until the very end, was supine (with the notable and consistent exception of brave investigative journalists.)

But it’s particularly easy to see today.

The quintessential act of cowardice in the Trump era is quoting him on face value.

James Risen, the ferocious investigative journalist who exposed the Bush warrantless wiretapping scandal, expressed his frustrations recently on “Democracy Now”:

The thing about Donald Trump is he lies about everything all the time, and that one of the real problems I have with the press today is that we actually — that the mainstream press quotes him all the time, knowing that he’s lying about everything, and continues to treat him like he’s really the president, when he’s just an illegitimate criminal, and he lies about everything. So why are we constantly quoting him and quoting his tweets and his statements, when you know that everything that comes out of his mouth is a lie?

Calling Trump an illegitimate criminal may be a bit much to ask news reporters, but all the stenography that they do is tantamount to journalistic malpractice – and is, at its heart, an act of cowardice. Too many fine, highly-credentialed reporters are simply terrified of appearing biased, scared of being attacked by the right, afraid of pissing off sources – and, perhaps most importantly, terror-stricken at the prospect of upsetting their editors.

And yes, they know better. It’s inarguable that Trump often lies, impulsively reverses himself, speaks incoherently and doesn’t seem to grasp the basics. Similarly, as this recent Post story suggests, the risks he poses to constitutional order are well understood by the press corps. The story notes that “the administration has run roughshod over Congress, prompting concerns among constitutional experts and lawmakers that Trump’s hostile stance toward congressional oversight is undermining the separation of powers in a way that could have long-term implications for democracy.”

They know what a mockery the administration is making of the press corps itself. They say it to each other privately. Sometimes it gets picked up on a hot mic.

But it’s not reflected in the daily coverage.

All it would take is a paragraph or two.

Hiding in Plain Site

Trump is not stealthy. Recently, he has taken to openly discussing what are by any normal standard blatantly impeachable events.

But the timidity of the press corps has turned that into an act of genius.

As part of an occasional Washington Post series “offering a reporter’s insights,” White House correspondent Ashley Parker marveled at how Trump’s “controversial public disclosures” have become almost routine – “a form of shamelessness worn as a badge of protection — on the implicit theory that the president’s alleged offenses can’t be that serious if he commits them in full public view.”

And Parker acknowledges that it’s working:

Trump’s penchant for reading the stage directions almost seems to inoculate him from the kind of political damage that would devastate other politicians.

But that shouldn’t inoculate him at all.

Here’s how James Poniewozik, the New York Times TV critic, explained it:

There are a lot of factors in this, but I think a big one is that covering an out-in-the-open scandal requires saying: "This thing that we all saw, in broad daylight, is actually scandalous," and that makes people nervous that it sounds like "taking sides."

— James Poniewozik (@poniewozik) October 3, 2019

Jon Allsop (@jon_allsop), Jon Allsop, writing in the Columbia Journalism Review, agreed:

The press, on the whole, does not consistently use language commensurate with overt wrongdoing. (The Times’s print headline this morning, calling Trump’s admission a “brash public move,” is a case in point; so was Jonathan Karl’s claim, on ABC, that “this is becoming less a question of what the president did than a debate over what is right and what is wrong.”)

Over the summer, Washington Post media critic (and former New York Times public editor) Margaret Sullivan (@sulliview), blasted reporter for tiptoeing around Trump’s racism, among other things. She asked, poignantly:

Are journalists going to embrace or abandon their primary job, which is truth-telling?

If they are going to do that job, they must embrace direct language and clear framing of important issues.

That, she wrote, means making the choice to use the obvious words:

It depends on only one thing: whether journalists want to be clear about saying what’s right there in front of everyone’s eyes and ears….

It makes good sense for media organizations to be careful and noninflammatory in their news coverage. That kind of caution continues to be a virtue.

But a crucial part of being careful is being accurate, clear and direct. When confronted with racism and lying, we can’t run and hide in the name of neutrality and impartiality. To do that is a dereliction of duty.

Though Sullivan didn’t mention it, there’s a third topic reporter sare even more wary of addressing than Trump’s racism and lying, and that is Trump’s mental health. Progressive columnist Eric Boehlert (@EricBoehlert), calls it “the media’s holy trinity of timidity under Trump — newsrooms refusing to call him liar, racist and unstable.”

the media's holy trinity of timidity under Trump — newsrooms refusing to call him liar, racist and unstable. @amjoyshow pic.twitter.com/eFTCINJFxI

— Eric Boehlert (@EricBoehlert) August 26, 2019

“The problem for so many journalists and news organizations is that once you do one of those things – call him a liar, call him a racist, question his mental stability – that has to the only story the rest of his presidency,” Boehlert said on MSNBC. “You can’t walk that back. And they don’t want that fight for the next 15 months.”

The Most Obvious Whiffs

Nothing brings out the press corps’ extraordinary lack of courage more than the rare sit-down interviews with Trump. A sit-down interview is the best opportunity journalists have to confront Trump with the realities he chooses to disregard, challenge him on his lack of informed policy views, and push back on his his lies. But doing that would also guarantee they’d never get invited back.

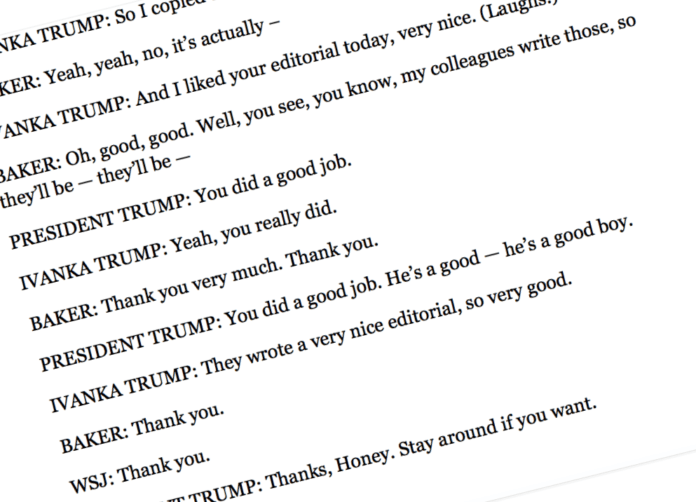

Many top news organization refuse to publish the full transcripts of their interviews — and the leaked transcript of a 2017 Wall Street Journal interview shows why. Then editor-in-chief Gerard Baker responded to Trump’s compulsive, obvious fabrications with obsequious bonhomie and not the slightest pushback.

Sitting down for an interview with someone who lies to your face — and not confronting them with the truth — is spineless enabling.

Local Reporters Have More Grit

Here’s a marvelous Twitter thread from Columbia Journalism School Professor Bill Grueskin (@BGrueskin):

Watch this interview of Mike Pompeo by Nashville reporter @WSMVNancyAmons. Pompeo seemed to expect softball treatment from the local NBC affiliate.

Instead, he got grilled like a rainbow trout on a bed of hot coals.

Really, WATCH this. https://t.co/EQmAhpg2gL 2/

— Bill Grueskin (@BGrueskin) October 12, 2019

I now show this @JvittalTV interview of Sen. @RandPaul to all @columbiajourn students. Vittal, of @NY1, does NOT take no for an answer, and chases Paul down the stairs to find out why he's holding up a bill to help 9/11 first responders.https://t.co/cxeAHvYPFE 4/

— Bill Grueskin (@BGrueskin) October 12, 2019

Sure, beltway journalists often break stories, and piss off officials, too.

But importantly, local reporters don't live and die by ingratiating themselves with sources, or clinking glasses with senators at Maureen Dowd's Georgetown parties.

They payoff is worth it. 6/6

— Bill Grueskin (@BGrueskin) October 12, 2019

The Indignities

The poor, benighted correspondents who actually work out of the White House press room and follow Trump around have been reduced to mere props. But when Trump says jump, they do.

Consider “chopper talks”. They are a farce. As Michael Calderone and Daniel Lippman wrote in August for Politico:

They allow him to speak more often in front of the cameras than his predecessors, yet firmly on his own terms. He scans the pack of reporters, seizing on questions he wants, while ignoring others. He makes headline-ready pronouncements and airs grievances for anywhere from a few minutes to a half-hour — and then walks away when he’s had enough.

Paul Farhi wrote in the Washington Post in October:

The format is a win-win for Trump, enabling him to grab the spotlight while marginalizing the press, both aurally and visually….

In all, the chopper gaggles are “a dominance ritual,” says Todd Gitlin, a professor at the Columbia School of Journalism. “It’s set up to make him look like he’s in command, and he’s lording it over [the news media].”

The format also effectively precludes the only kind of question that has any potential value when Trump is involved: Follow-up questions. The reporters can’t even hear what Trump is saying sometimes.

And yet the press corps participates eagerly. They literally run. (“White House correspondents eagerly scramble to cover Trump’s South Lawn appearances, sometimes leading to disorderly scenes,” Farhi wrote.)

They could, say, just send one intern. But they run.

And the cable networks show these performances, some of which last 10, 15, 20, even 25 minutes, in their entirety, uninterrupted, as soon as the video is available.

What the Fuck?

It’s the faux naïveté of a timid reporter that triggered Democratic presidential candidate Beto O’Rourke’s August display of unvarnished media criticism in the wake of the immigrant massacre in El Paso. A hapless reporter asked him a question so lacking in spine it was irresponsible: “Is there anything in your mind the President can do to make this better?”

O’Rourke famously replied:

What do you think? You know the shit he’s been saying. He’s been calling Mexican immigrants rapists. I don’t know, members of the press, what the fuck?… Hold on a second. You know, it’s these questions that you know the answers to. I mean, connect the dots about what he’s been doing in this country. He’s not tolerating racism; he’s promoting racism. He’s not tolerating violence; he’s inciting racism and violence in this country…. I don’t know what kind of question that is.

Veteran media observer and professor of journalism Jeff Jarvis (@jeffjarvis) translated O’Rourke’s criticism into some simple guidelines. Among them:

Tell the truth. Speak the word. If you prevaricate, refusing to call what you see racism or what you hear lies, you give license to the public to do the same and give license to the racists and liars to get away with it.

Stop getting other people to say what you should. It’s a journalistic trick as old as pencils: Asking someone else about racism so you don’t have to say it yourself…

You are not a tape recorder. Repeating lies and hate without context, correction, or condemnation makes you an accessory to the crimes. That goes for racists’ manifestos as well as racists at press conferences.

Do not accept bad answers. Follow up your questions. Follow up other reporters’ questions. Just because you’ve checked off your question doesn’t mean your work here is done…

Be honest. The standard you work under as a journalist — the thing that separates your words from others’ — should be intellectual honesty. That is, report inconvenient truths.

Gutsy journalism isn’t just good journalism – it’s essential to the proper functioning of our country. Journalists who would rather blame both side, or blame no one, or “let the reader decide” rather than state what they know to be true do a terrible disservice.

After all, how can democracy self-correct if the public does not understand where the problem lies?